Marking time in October 2013

Symbolising AMSA

I follow the @AMSAupdates Twitter feed for news about the Australian Maritime Safety Authority’s work. These tweets don’t appear every day, but they are usually about something important and interesting—a search and rescue operation, a lighthouse repair, a medical evacuation, or a training exercise.

It’s good to see that AMSA has chosen my old favourite, the North Reef lighthouse, as the icon for this feed. The recently conserved lighthouse also appears in the background of the web page.

Sawing backwards

One of the best things about the recent refurbishment of the Brisbane City Hall is the new accommodation for the Museum of Brisbane. The museum is up on the roof of the building, hidden neatly behind the parapet, with views of the central dome.

There is a new exhibition about the Brisbane River, which includes this painting by Cedric Flower. The painting was the headline work in a commercial exhibition in 1965—Select views and scenes of Brisbane life: 1830-1900 by Cedric Flower—shown at the Johnstone Gallery. The picture catches the character of the haphazard little settlement in a landscape dominated by the river. The exhibition catalogue notes that it was painted after a drawing by an unknown artist in the possession of the Mitchell Library.

That unknown artist is believed to be Henry Boucher Bowerman (1789–1840), a civil servant who worked in the Commissariat at Moreton Bay in the early 1830s and who had studied topographic sketching at the British Military Academy at Woolwich. A few of his Brisbane Town drawings have found their way into public collections in Brisbane, Sydney and Canberra.

Flower’s painting (450 × 900 mm) is larger than the Bowerman drawing (150 × 300 mm) and has added colour and various small details. Flower has added a group of Aboriginal people to his picture—these people, a column of smoke floating up from the brick kiln, and a white person with a fishing rod, all enliven the picture.

One detail of special interest to me is the sawpit near the river bank below the windmill. Flower has nicely copied the hipped roof over the pit, the three sawyers, the logs awaiting sawing, and the sawn boards stacked for seasoning.

But Cedric Flower has drawn all three sawyers standing on the wrong side of their saws. I guess if he had ever tried pit sawing, he wouldn’t have sentenced these convicts to such cruel and unusual treatment.

What Alex Symons did next

I have kept searching for information about Alex Symons, the purser of the steam yacht Merrie England. Two accounts have turned up, both written by men who worked with him in British New Guinea in the 1890s.

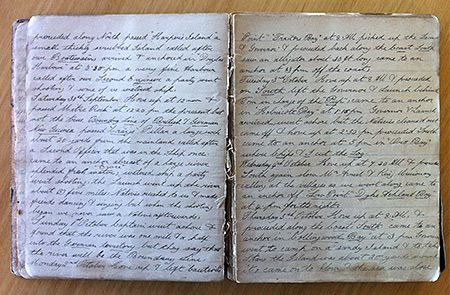

The first is the diary of Henry Mitchell, a crew member on the Merrie England in 1893–1895, now in the John Oxley Library.

So far, I have only skimmed the diary, to get an idea of what’s in it. Alex Symons is mentioned. I’ll be back for a closer reading—easy for me, since I live within walking distance of the library.

For readers from further away, the diary deserves to be digitised and transcribed. The transcription would take some time—time well spent, in my opinion. The diary is packed with dates, places, events, and people (Papuan and European) from the time when colonial authority was first asserted in Papua—details that make it an important resource for historical research. It’s a candidate for crowdsourced volunteer transcribing, tagging, checking and editing—I’d be willing to do my bit. I’d even be willing to do some semantic markup to add extra richness to the text.

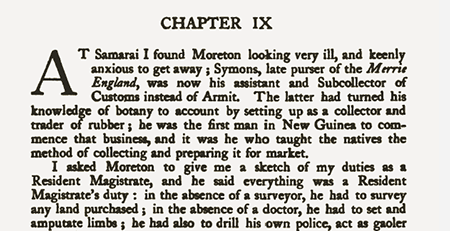

My second source of information is a book by Captain C A W Monckton, Taming New Guinea: some experiences of a New Guinea Resident Magistrate (New York: John Lane Company, 1925), which is available online.

Monckton’s book is a ripping yarn of adventure in the colonies. The story begins in Cooktown in 1895 where Monckton found himself at the age of 23, armed with £100, an outfit particularly unsuited to the tropics, and a letter of introduction from the then Governor of New Zealand, the Earl of Glasgow, to the Lieutenant-Governor of British New Guinea, Sir William MacGregor. When he met the governor, Sir William had no job to offer anybody who was not conversant with native customs and ways of thought. He recommended that Monckton come back after he had got some experience of life in New Guinea. Monckton set off to get that experience—through gold mining, trading, ship-owning, bar tending and other odd jobs around the colony—before being appointed by the governor as a resident magistrate at Samarai in 1897. While he was in that service he met Alex Symons.

Symons had left the Merrie England and been appointed to various government posts on shore—this happened before Monckton was appointed. Monckton gives him an unflattering assessment and recounts one episode in which Symons, while a magistrate, was with a party of European gold miners who murdered a Papuan man. Symons did not act to prevent the crime or apprehend the perpetrators. Monckton was involved in discovering what had happened, and in bringing Symons to book.

Symons, the man responsible for the state the district had got into, was reduced from magisterial rank, and sent as a clerk to the Treasury; the fact of his being a married man with a family being taken into consideration by Sir George.

I expect there is much more to be found out about Alex Symons. I’ll keep searching.