Marking time in July 2013

The rowdyism and brutality of the uneducated and ill-bred

As I was searching for references to the Merrie England in the Australian newspapers, I turned up a piece of moralising titilation which connected that steam yacht with stories of Victorian scandals. The commentary was prompted by the death and life of George Baird, one of Lillie Langtry’s lovers, but it also mentioned Mr Bailey for whom the Merrie England was originally built.

The piece was printed in the Melbourne Argus of 6 May 1893, set in one breathless paragraph in the middle of a gossip-column. I have cut it into chunks for easier reading:

VANITY FAIR

By J.M.D.

London, March 29

[Three paragraphs snipped: a piece of political gossip, art exhibition reviews, a divorce]

The memory of Mr G Abington Baird [sic] is still kept fresh by rumours of lawsuits and complications arising out of his will. The latest version of the affair is that Baird made a will leaving Mrs Langtry £50,000 a year, but forgot to sign it. Of course, even the public rumour that the lady has narrowly escaped receiving £50,000 a year so very easily must be exceedingly fascinating.

The press generally has been rather savage in criticism of the deceased youth. The Daily Chronicle makes him a text for a coarse and vindictive stump oration about the vices of the propertied classes and the aristocracy. Of course Abington Baird’s manners and customs and whole career were simply the recrudescence in the third generation of sheer rowdyism and brutality inherited from ancestors who were uneducated, drunken, brutal colliers and quarrymen. His craze for whisky and for beating women was thus inherited. He had far more in common with the “lucky digger” of the early alluvial gold-mining days in Australia fifty years ago than with the Duke of Hamilton, the late Earls of Westmoreland and Stamford and Warrington, Sir John Stanley, of Hooton, and other famous spendthrifts of aristocratic birth.

The fact is that the Baird type—minus the jockeyship—is exceedingly common, especially in the North of England. Fortunes are suddenly made there by working people, by very poor people, much offener than is supposed. Now and then this sort of thing will happen—the father, a working man, makes a lot of money, say out of some successful patent; he and his wife then proceed to drink themselves to death with great celerity, and the son comes in for the fortune. As a rule, the first thing he does is to buy, or order, a large steam yacht to take his pals about in.

That fine steam vessel, “The Merrie England,” which is at the service of Sir William MacGregor, the administrator of New Guinea, had such an origin as this. The youngster who ordered it “bust up” before it was completed, and the Treasury bought “The Merrie England,” a great bargain, from the ship-builders.

A few years ago a young fellow called Brooke, the son of a working man who had suddenly grown enormously rich by some lucky speculation, made a tremendous splash for a while in the West End. He used to give large supper parties, at which there was nothing whatever to eat, but illimitable supplies of champagne and cigars. He is dead.

[Five more paragraphs snipped: review of a public lecture, death of the Duke of Bedford, birthday of a war correspondent, a society wedding, a diplomatic appointment]

More about the heliograph

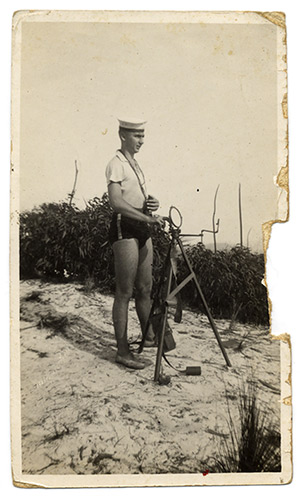

For the record, I have identified the heliograph my father is using in the photo I showed here the other day.

It is a British Mance type heliograph, mark V. On the web are pictures, more pictures, a copy of the 1905 handbook, and the memoirs of a Second World War British army signaller—who remembers the special excitement of using the heliograph during a training session on the golf links overlooking the Firth of Forth in the early 1940s, when with the aid of a bright moon the heliograph worked well and the signals could be read clearly.

Best of all, here is a set of cigarette cards published in 1911 that explain the whole business—something we will not see again, in this new era of plain packaging…

The purser of the steam yacht ‘Merrie England’

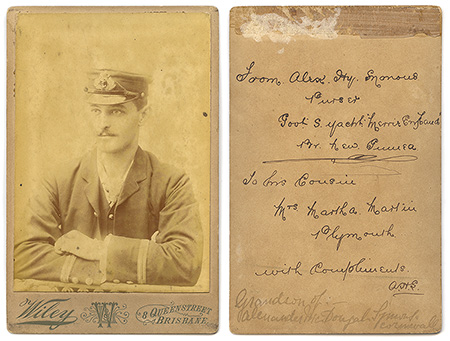

Since Papua New Guinea is in the news, I’ll mention a cabinet photograph I recently bought from a dealer in England. It’s a portrait of a handsome young man wearing a naval officer’s cap and coat. It suggested a few lines of inquiry.

Let’s start on the front of the photo. The studio name, Wiley, a large decorative W, and the address 8 Queen Street Brisbane are printed at the bottom. These give us clues about when the portrait was taken. Davies & Stanbury say that John Wiley was at that address from 1890 to 1894.

I searched newspaper advertisements to get more precise dates. On 26 April 1890 John Wiley advertised that he had bought the business of the Elite Photo Co at 8 Queen Street. He kept using the Elite Photo Studio name, linked with his own, until about February 1891. I guess he benefited from the goodwill of the Elite name, and was obliged to wait for a month or two while a stock of card mounts was printed with the Wiley name. This suggests mid-1890 as the earliest date for our portrait.

Davis & Stanbury say that Wiley moved next door to 10 Queen Street after 1894. But the newspapers don’t agree. The record seems clear that Wiley stayed in the same premises at 8 Queen Street until he formed a new partnership and, as Wiley & Sturgess, moved to Lomer & Co’s old studio at 158 Queen Street in March 1905.

So, the portrait was taken after about June 1890, and before March 1905.

On the back of the card are more clues. There is a dedication (written by the young man in the picture, I assume): From Alex. Hy. Symons: Purser: Govt. S. yacht ‘Merrie England’: for New Guinea: To his Cousin: Mrs Martha Martin: Plymouth: with Compliments: A.H.S. A note in a different hand and lighter ink says Grandson of Alexander McDougal Symons, Cornwall. The purser is the ship’s officer responsible for keeping the ship supplied with food, drink and other goods.

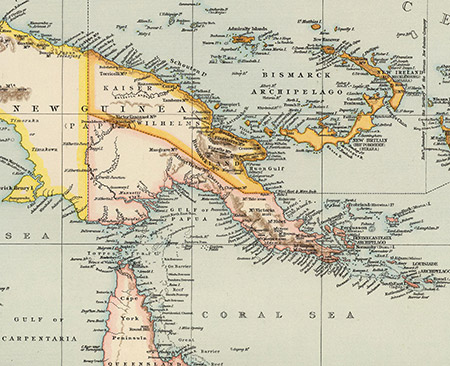

I had not known about the Merrie England, but found lots of references in the newspapers. This is from the Sydney Morning Herald, 25 February 1889:

The Colonial Office have just purchased two small steamers for the use of the New Guinea administration. One is a boat that was used during the Nile Expedition, and is of light draught, so as to be suitable for river and inland navigation, and the other is a yacht of some 411 tons burden. This latter vessel … is called the Merry England. At present it is stationed in the East India Docks, but it is expected to be ready to start for the colony in about a month’s time.

The Brisbane Courier, 26 April 1889, had a long article headed ‘Steam yacht for New Guinea service’ (I have broken the rather dense text into paragraphs to make it easier to read on screen):

The steam yacht Merrie England, which was purchased by the Imperial Government for the New Guinea service, and left London about the end of February, is daily expected to arrive at Thursday Island.

It will be remembered that by the terms of the British New Guinea (Queensland) Act the Imperial Government agreed to contribute a suitable steam vessel for the service of British New Guinea at a cost not exceeding £18,500, with the cost of its maintenance during the first three years, estimated at about £3,500 per year. In October last the Acting Governor, Sir Arthur Palmer, requested the Secretary for State to purchase a steam yacht for New Guinea, and it appears considerable difficulty was experienced in finding a suitable vessel, owing to the necessity for her being either composite or wood, and also for her not drawing too much water.

Early in November the Merrie England, belonging to Mr Bailey, of Hull, was examined at that port by the Admiralty surveyors; by Captain Almond, despatch officer of the Queensland Government, and by Lloyd’s surveyors. The vessel was found to be in a thoroughly satisfactory condition in every respect, and it was decided that with certain alterations she could be rendered suitable for the purpose for which she was required. The purchase was completed on 3rd January, the price paid being £8,500.

The following is a description of the vessel as purchased. She was built in 1888 by Ramage and Ferguson, of Leith. Her length is 147 ft; beam, 25 ft 2 in; depth, 13 ft 4 in; draft of water, 13 ft 0 in aft, and about 10 ft forward; headroom in cabins, 7 ft 0 in; registered tonnage, 170 tons 6 cwt; gross, 259 tons 8 cwt; yacht measurement, 411 tons; displacement, about 400 tons; engines, two inverted compound, by Ramage and Ferguson—diameter of cylinders, 17 in and 34 in; length of stroke, 22 in; nominal horse-power 60, indicated about 260; present speed under steam, 9 knots; consumption of coal, 4½ tons per twenty-four hours; bunker capacity, about 75 tons; fresh water, 7 to 8 tons; ballast, 20 tons of lead on keel, and about 60 tons of iron and lead in hold.

A number of alterations have, however, been made since the purchase. The spars have been reduced in size, and the sails and rigging altered to correspond. The hull has been stripped, caulked, and recoppered, and the top sides painted light stone colour. Several inches have been taken off the keel, and the ballast reduced so as to bring the draught to 12 ft 6 in. The funnel has been lengthened, and a new four-bladed gun-metal propeller has been fitted with four spare blades and spare tail shaft instead of the original two-bladed feathering propeller. This alteration has increased her speed to over 10 knots. The large cutter, 25 ft by 6 ft, has been converted into a steam launch, and a new whaleboat supplied, with all necessary awnings and gear; she has also a four-oared gig and a dingy.

The original inventory of the vessel was complete for a yacht, but in addition she has been fitted with double awnings, punkahs, ice-making machine, and all other stores and necessaries, in order to render her suitable for service in the tropics for a long period without further outlay. A duplicate main-crank shaft and other spare engine fittings and stores have also been provided.

She is armed with a three-barrelled Nordenfelt quick-firing gun, Martini-Henry carbines, revolvers, and cutlasses, with a large supply of ammunition.

Captain Hampton, late of the SS Barcoo, who took the Waroonga home, and has lately been engaged in supervising the building of several new steamers for the BISN Company for service on the Queensland coast, has been engaged to bring the Merrie England out on account of his intimate knowledge of New Guinea and Northern Queensland waters.

It was at first intended that the Merrie England should be taken direct to Port Moresby, but we understand that it is in contemplation to bring the vessel down to Brisbane and have her completely overhauled previous to beginning service in Now Guinea waters. There is a possibility that his Excellency the Governor of New Guinea, who is about to visit Brisbane, will return to New Guinea by the Merrie England after her overhaul.

On the delivery trip the Merrie England stopped at Thursday Island in early May 1889 and from there went on to Port Moresby to bring the Administrator of British New Guinea (Dr Macgregor) to Brisbane. The Brisbane Courier, 24 May 1889, takes up the story:

On arriving there, however, it was found that Dr Macgregor was still absent exploring the Owen Stanley Range, and was not expected back for a fortnight. As Captain Hampton had to leave, and the crew had to be recommissioned, the Merrie England came on to Cooktown. Captain Hampton is now bringing the vessel to Townsville for coal. He will resign his command of the vessel shortly, as he has to return to England by the steamer Taroba to bring out anothor steamer for the BISN Company. Mr Atkinson, chief officer of the Lucinda, who has been appointed to the acting command of the Merrie England, will leave on Saturday for Townsville by the steamer Maranoa to take charge of the vessel, which will proceed at once to Port Moresby to bring Dr Macgregor to Brisbane.

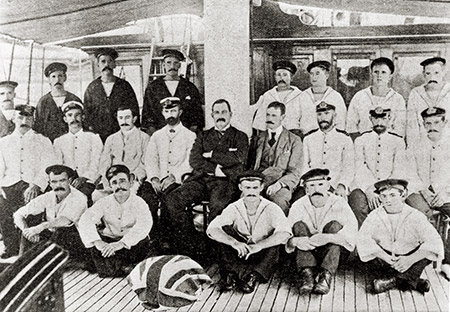

William Macgregor, administrator and later lieutenant-governor of British New Guinea, was an energetic colonial administrator. The newspapers have many accounts of his journeys, on land and on board the Merrie England—exploring the country, facilitating the work of colonisers and missionaries, and bringing British law.

The Merrie England first came to Brisbane on 31 July 1889, and left on 11 September. Here is a list of later more-or-less-annual comings and goings recorded in the newspapers:

- 1890

- arrived 6 September, left 25 October

- 1891

- arrived 14 October, left 25 November

- 1892

- floated out of dry dock 2 November, on trials in Moreton Bay 26 November, left 3 December

- 1894

- arrived 17 July

- 1896

- in dry dock 5 February, expected to leave in the next week 25 February

- 1897

- berthed at Port Office wharf 19 March

[Update: Alex Symons was no longer on board the yacht after 1897] - 1898

- arrived 24 December

- 1899

- arrived 1 March, left 11 March

in dock 31 July - 1901

- moored in the river 12 September, in dock 16 September, left 2 November

- 1902

- arrived 23 July, left 13 October

- 1903

- arrived 12 March, left 1 May

- 1904

- arrived 19 April, in dock 7 June, still in dock 22 June, in Sydney 26 July

Alex Symons might have been photographed in Wiley’s studio during any one of those visits.

Moon signals at Bustard Head

I found this in the Queensland Figaro newspaper, 24 September 1903. The same story also ran in the Launceston Examiner, the Wagga Wagga Advertiser, the Melbourne Argus, the Hobart Mercury, the Zeehan & Dundas Herald, and the Rockhampton Morning Bulletin:

Moon signals

It was while locum tenens at the rectory of Gladstone, Queensland (says a writer in Chambers’ Journal for August) that I became aware that moon-signals could be used in the same way as those of the sun. It was my duty to go to Bustard Head Lighthouse every few months to hold service and visit the Sunday-school and people of the station. I usually went by land, and rode 30 miles to Turkey Station; and as soon as I arrived Miss Maud Worthington, the daughter of the station owner, would at once heliograph the news of my arrival at Bustard Head, and enquire by use of an 8 in looking glass at what time a horse could be sent to meet me on the other side of the swampy ground, over which it was wiser to walk. There I was met by Mr Rookesby and his wife, who piloted me to the lighthouse station. Mr Rookesby is a well-known inventor in Queensland. He erected the heliograph between Turkey Station and the lighthouse, but failed to make communication with Gladstone, 84 miles off, either because an 8 in mirror was too small, or because of other conditions peculiar to the lie of the country. He then experimented with signalling by moonlight, and discovered that—notwithstanding the feeble light of the moon as compared with sunlight—owing to the darkness of the night, the moon’s reflections were quite powerful enough to carry the intervening 10 miles between the two stations.

A heliograph, of course, is a gadget for sending text messages by using a mirror to reflect the sun’s (or moon’s) rays towards the person receiving the message. By pivoting the mirror back and forth the operator can send a series of long and short flashes to transmit the message by Morse code.

A severe blow

A while ago in Dunedin I visited the Otago Settlers Museum, an institution founded in 1898, the 50th anniversary of the first Scottish settlement of Otago. In the beginning the museum focused on the earliest European arrivals—from 1848 until 1861 when the gold rush started. The focus gradually widened to acknowledge more recent arrivals and, eventually, the Māori people who had been there all along. In 2012 the museum was renamed Toitū Otago Settlers Museum. Toitū is the Māori name of a stream that once flowed near the site, and the word carries other connotations, as the museum website explains.

In the museum is an ‘early colonists’ gallery, purpose-built in the early 1900s. In this large square room, lit by lantern windows at the top of the hipped ceiling, there are hundreds of framed photographs stacked six rows high. It’s very impressive, and gives the impression that anybody who can’t point to an ancestor on the wall is a newcomer.

I was reminded of my visit by the Early New Zealand photographers blog, which quoted this newspaper article:

The war and the rising value of glass has combined to administer a severe blow to the Canterbury Early Colonists Committee. The gallery of photographs of old colonists in the Museum is feeling the effects of time, and many of the portraits are fading. The idea struck a member of the committee that it would be a good scheme to get fresh copies made of some, or all, of the portraits, and he made enquiries from the Christchurch photographer who had the negatives to see what could be done in the matter. He was amazed to learn that, owing to the value of glass. Sydney agents had been round to most of the photographers in Christchurch and bought up old negatives at 3d a dozen, and about 300 portraits of the old Canterbury identities were among the negatives secured.

[‘General News’, The Press (Christchurch newspaper), 22 July 1916.]

It’s a terrible warning about who you can trust to look after your most precious stuff. And in this time of digital storage it’s a warning about entrusting anything to the cloud.