Marking time in April 2013

More about the woodburytype

To add to my terse mention of the woodburytype the other day, I bring you a paragraph of text, and a video.The paragraph is from Richard Benson’s book The printed picture [New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2008]:

The woodburytype plate was hard to make, but once done it could generate a lot of inexpensive prints. They curled terribly and the borders were always a mess, from the excess gelatin squeezing out, so they were always mounted. The woodburytype used no silver, which saved money, and it could produce monochromatic prints in any color, according to the pigment used. The prints were also never wet, so all the complex handling of wet paper was avoided. Most of them were colored to imitate albumen prints, so the viewers believed they were seeing a “real” photograph. The technology didn’t allow prints much bigger than eight by ten inches [20 x 25 cm], but these beautiful little prints never had to go into a hypo bath so they are remarkably permanent.

This video from George Eastman House shows the woodburytype printing process in action:

Pricing timber

I have scanned a pair of timber price lists from my collection. See the PDFs here. They were produced in the 1930s by timber merchants in Queensland and New South Wales. They allow some interesting comparisons.

One example: The Sydney supplier (Vanderfield & Reid Ltd) offered many timbers imported from overseas—Oregon (Douglas Fir), Redwood, Yellow Pine, Sugar Pine and Hemlock from North America; Baltic Pine from Europe; Rimu and White Pine (kauri?) from New Zealand; Pacific Maple from Asia; Pacific Oak from Japan; and Gaboon Mahogany from Africa.

In contrast, almost everything sold by Hancock Brothers was cut in Queensland. The few imports came from America—Oregon (up to 60 feet long, while 40 feet was the maximum for Queensland Pine); and Redwood shingles.

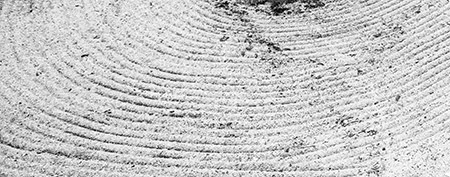

Zen raking

First thing in the morning. I’m on the verandah of the Assistant Lightkeeper’s quarters. I can hear waves lapping the shore, sea birds calling, the wind in the palm fronds. At a distance, just audible, repeated strokes of a rake on sand.

Jenni and Wayne, the caretakers, rake the sand paths at Low Island. They remove fallen leaves and twigs, and mark the damp sand with a hatching of rake marks. They call it zen raking, with a laugh at themselves, but I sense this meditative task sets them up for the day.

The first visitors of the day arrive mid-morning. As they go from place to place their footprints make a dot-painting of their routes. By mid-afternoon they are back on the boat and away. The footprints stay overnight, blurred by wind and rain, for Wayne and Jenni to erase the next morning.