Marking time in November 2012

Piggyback princess

In September 1868 Princess Alexandra was photographed with her baby daughter Louise riding piggyback. The picture makes the princesses look like ordinary people. Perhaps because of its charming informality this photograph, published as a carte-de-visite, was a best seller. Loyal subjects, in their hundreds of thousands, bought copies to put in their albums. One of these has found its way into my collection.

This photograph reminds me of carte-de-visite albums and the place of celebrity portraits in them. As well as portraits of family and friends, there were pictures of actors, opera singers, and circus freaks. And royalty.

Those albums are fast taking the place and doing the work of the long cherished card basket. That institution has had a long swing of it. It was a good thing to leave on the table that your morning caller, while waiting in the drawing- room till you were presentable, might see what distinguished company you kept, and what very unexceptionable people were in the habit of coming to call on you. But the card-basket was not comparable to the album as an advertisement of your claims to gentility. The card of Mrs. Brown of Peckham would well to the surface at times from depths to which you had consigned it, and overlay that of your favourite countess or millionnaire. Besides, you could not in so many words call attention to your card-basket as you can to the album. You place it in your friend’s hands, saying, “This only contains my special favourites, mind,” and there is her ladyship staring them in the face the next moment. “Who is this sweet person?” says the visitor, “Oh, that is dear Lady Puddicombe,” you reply carelessly. Delicious moment! [‘The carte de visite’, All the year round, 26 April 1862].

To go with the famous carte-de-visite of the princesses, I have another which might have been prompted by it. The photo was taken in the studio of J Weston & Son of Folkstone, but I do not know who the subjects were. I can imagine the mother asking the photographer to take a photo ‘with my daughter on my back, just like Princess Alexandra’.

According to the Sussex PhotoHistory website Jasper Weston’s son Frederick joined the studio about 1874. So this second photo was taken after the royal photograph had been in circulation for a few years.

More about sawyers

To continue on the subject of sawyers—Roger Dean has just posted a beautiful photograph of some shipwrights in bas relief, paired with this quote from Henry Mayhew:

According to the last census the number of sawyers in Great Britain in 1841 was 29,593; of these 23,360 resided in England, 4,550 in Scotland, 1,508 in Wales, and the remaining 175 in the British Isles. About one-tenth part of the whole of the sawyers in Great Britain were then located in the metropolis, the number in London being 2,978, of whom only 186 were under twenty years of age. Strange to say, one of the sawyers above twenty was a female!

[…] Of sawyers there are four kinds—viz., the hardwood and timber sawyers, the cooper’s stave, and the shipwright sawyers. The hardwood sawyers are generally employed in cutting mahogany, rosewood, and all kinds of foreign fancy woods. This work demands the greatest skill in sawing. It requires special nicety in cutting, because the timber is more valuable, and a ‘bungler’ might be the cause of great loss to his employer. A hardwood sawyer can generally turn his hand to timber sawing, but the timber sawyers are seldom able to accomplish the cutting of hard woods. Timber sawyers are mostly engaged in cutting for carpenters and builders. The work of the cooper’s stave sawyers consists principally in cutting ‘doublets’ out of the foreign wood. The shipwright sawyers cut the ‘futtocks’ and planks for ships.

Henry Mayhew—‘Labour and the Poor’, The Morning Chronicle—4 July 1850

A visit to the Eddystone Lighthouse

I feel guilty, just a little, because I support the vandals who cut up old books and magazines. I am part of that awful trade. I search for bits of paper on eBay, and I pay money to dealers. Forgive me.

But I rationalise that it’s a small transgression. If I don’t buy those bits of paper, somebody else will; and if nobody wants them, they’ll all go to landfill.

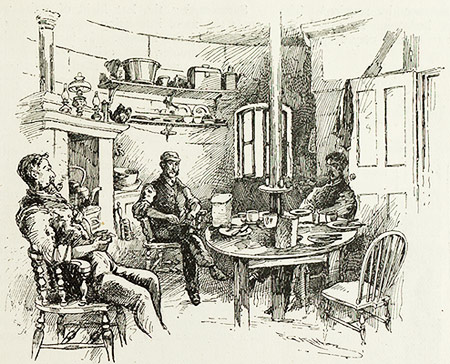

I paid a dealer to send me some pages pulled from a bound volume of the Strand Magazine (Volume IV, July-December 1892)—an article written and illustrated by F G Kitton, describing a visit to the Eddystone lighthouse. It’s a nicely written piece that gave me a peek into the offshore light keepers’ life.

Frederick George Kitton (1856–1904) was apprenticed to the London paper The Graphic as a wood engraver, and went on to work as a writer and illustrator. His special subjects were the novelist Charles Dickens and the town of St Albans.

The technology of printing was changing in the 1890s and the article shows the transition happening. Some of the illustrations are printed in the old way—the artist’s drawing painstakingly translated to the end grain of a boxwood block by a craftsman engraver. Other illustrations have been reproduced in the new way—the artist’s pen and ink drawings photographically copied and etched into a metal line block. The wood and metal blocks have been locked into the press along with the metal type to print an integrated whole. I enjoy the art of the wood-engraver, and the science of the photo-engraver, and I like to see both together in this article.

As penance for my part in the destruction of the bound volume, I have digitised the article, transcribed the text, and made a PDF copy of the pages (11,741 KB).