The carte-de-visite craze

Here is a little history lesson, which I hope will explain why I enjoy these artefacts.

What is a carte-de-visite?

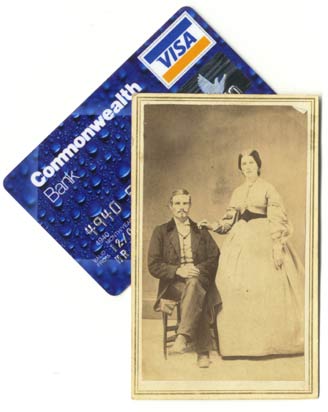

It’s a small black and white photo stuck to a card. It was invented in the 1850s, became a world-wide craze soon after, and faded away by the 1890s. Holding one of these little cards evokes the Victorian world’s social quirks and technological inventiveness.

Invention

In November of 1854, the French photographer André Disdéri introduced a method for producing multiple images on a single glass plate, a format for mounting the resulting images on cards, and the name carte-de-visite to describe the product. His invention caught on, and photographers around the world made it a lucrative business.

The business

The carte-de-visite business needed capital, technical skills, marketing savvy, specialised materials, cultural acceptance, and customer demand—in short, it was a system. It worked like this:

Promotion brought clients to the photographer. Posters, newspaper advertisements, a prominent studio and word-of-mouth brought clients to the door. In regions where the population was thinly dispersed (like rural Queensland) some photographers travelled in search of customers. These itinerant workers relied on newspaper advertising and, perhaps, a splash of showmanship to bring in the business.

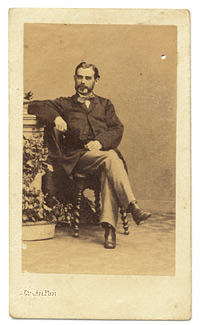

The studio was the place where it all came together. In established businesses, the photographer’s studio was an elegant setting for efficiently photographing a succession of sitters, and selling them as many photographs and accessories as possible. Customers were received in a waiting room, tasefully decorated with examples of the studio’s work. Sitters were then ushered into the camera room—a specially built room lit with skylights—where they were posed in front of the camera. They had to hold poses for several seconds, a feat made easier (if not more comfortable) by adjustable head clamps attached to posing chairs. The camera room had a range of painted backdrops, furniture, drapery and props to impart the right atmosphere to the picture—perhaps rustic, perhaps genteel.

The wet plate negative had to be sensitized before it was used in the camera. In this collodion process each glass plate was prepared in complete darkness, and exposed and developed while it was still wet. This complicated procedure was best done indoors in a properly set up darkroom. Travelling photographers resorted to horsedrawn vans or lightproof tents. See the video Making a wet collodion negative on the Getty website.

Multiple lens cameras made several small images on each glass plate negative. This cut the cost per image and simplified the handling of the wet plates. The photographer could choose to expose the images one after the other, or all at once—one of the keys to efficiency in the carte-de-visite business.

Albumen prints were made by contact printing the negatives. Albumen paper was made by coating each sheet with egg white. Yes, hens’ eggs—in 1862 a British firm used half a million eggs per year for this. The coated paper was sensitized with silver compounds.

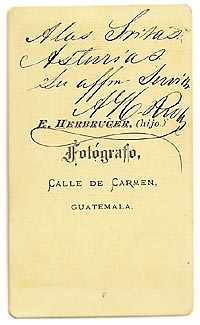

The card on which the print was mounted displayed the name of the photographer on the front and back. The back was often a showy piece of lithographic printing, with the photographer’s name decorated with curlicues. There was often a statement that extra prints could be ordered at any time, and sometimes the negative number was written on the back. A piece of tissue paper was glued on the back at the top, and folded over to protect the front of the print.

The craze

Disdéri’s invention was an immediate success.

Just as there is no serious question about Disdéri’s patent application, there is no doubt about his role in popularizing the carte de visite. An unverified story—no doubt embellished by tradition—relates how Napoleon III in 1859 en route with his troops to Italy, stopped at Disdéri’s Paris studio to have his portrait taken. Seizing the opportunity to make a handsome profit, Disdéri sold thousands of copies. Almost overnight a new fad was born. The studios of Paris, not only Disdéri’s, were besieged by patrons who wished to have their pictures taken in the new style. [William Darrah, Cartes de visite in nineteenth century photography]

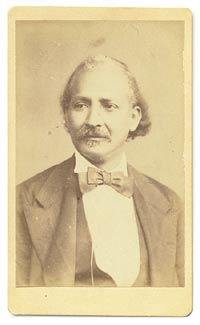

Ordinary people swarmed to the studios too. The little photographs were convenient to handle, sturdy, novel, and inexpensive. In an era of great social and economic change the new mode of photography spread from the metropolis to the hinterland. In the backblocks of Guatemala or Queensland, photographers set up their studios.

After the carte-de-visite

No craze lasts forever. The fad for cartes-de-visite faded in the 1880s, around the time George Eastman's Kodak camera was introduced. The Kodak slogan you push the button—we do the rest signalled the beginning of amateur photography for the masses.

More information

Cartes de visite in nineteenth century photography, a book by William C Darrah (self published in Gettysburg, USA, in 1981), is a comprehensive account. It's out of print now, but you should be able to find a copy in a good reference library.

Albumen photographs: history, science and preservation, a Stanford University website about ...the art and science of albumen printing. The site brings together 19th Century technical instruction, contemporary research, an online forum for conservation treatment and a wealth of images.

Carte de visite, an online exhibition on the Luminous Lint photo-history website. Sections of the exhibition deal with the carte-de-visite, the presentation of royalty, celebrities and occupations, the backs of cartes-de-visite, and albums and frames made for storing and displaying them.